It's now becoming obvious that the 5G Internet of Things promised by telcos a few years ago was nothing more than a way to sell a new generation of smartphones. For several reasons, not least being the cost involved, no IoT system widely distributed in the field can be based on devices with the power and maintenance requirements of 5G transmission.

The real future of IoT lies at the other end of the power/cost range in networks of cheap, low-power, long-range sensors based on a technology that overcomes signal interference among a large number of transmitters in close proximity and allows seamless provision and maintenance of the gateways used to provide backhaul to the internet or to local data processing systems.

New York City's FloodNet project is an early example of real-world IoT in action. To meet the increasing challenge of urban flooding, a network of sensors has been installed in flood-prone areas of the city to collect data on the presence, depth, and duration of street-level flood events.

The 81 sensors so far installed by the project communicate through a network of 17 gateways distributed across the five boroughs. They have already recorded flooding caused by high tides, stormwater runoff, storm surge, and extreme precipitation. The data is publicly visible and available in a form that can be used by multiple agencies for flood resiliency planning and emergency response.

The FloodNet project is an excellent example of appropriate technology. Existing water level sensors, such as those used by USGS stream gauges, are far too bulky and expensive to be deployed at scale across urban areas. The city needed cheap, accurate, weatherproof, real-time flood sensors designed for long-term unattended deployment independent of existing power and network infrastructure, adaptable to many use cases, and featuring a simple, open-source design.

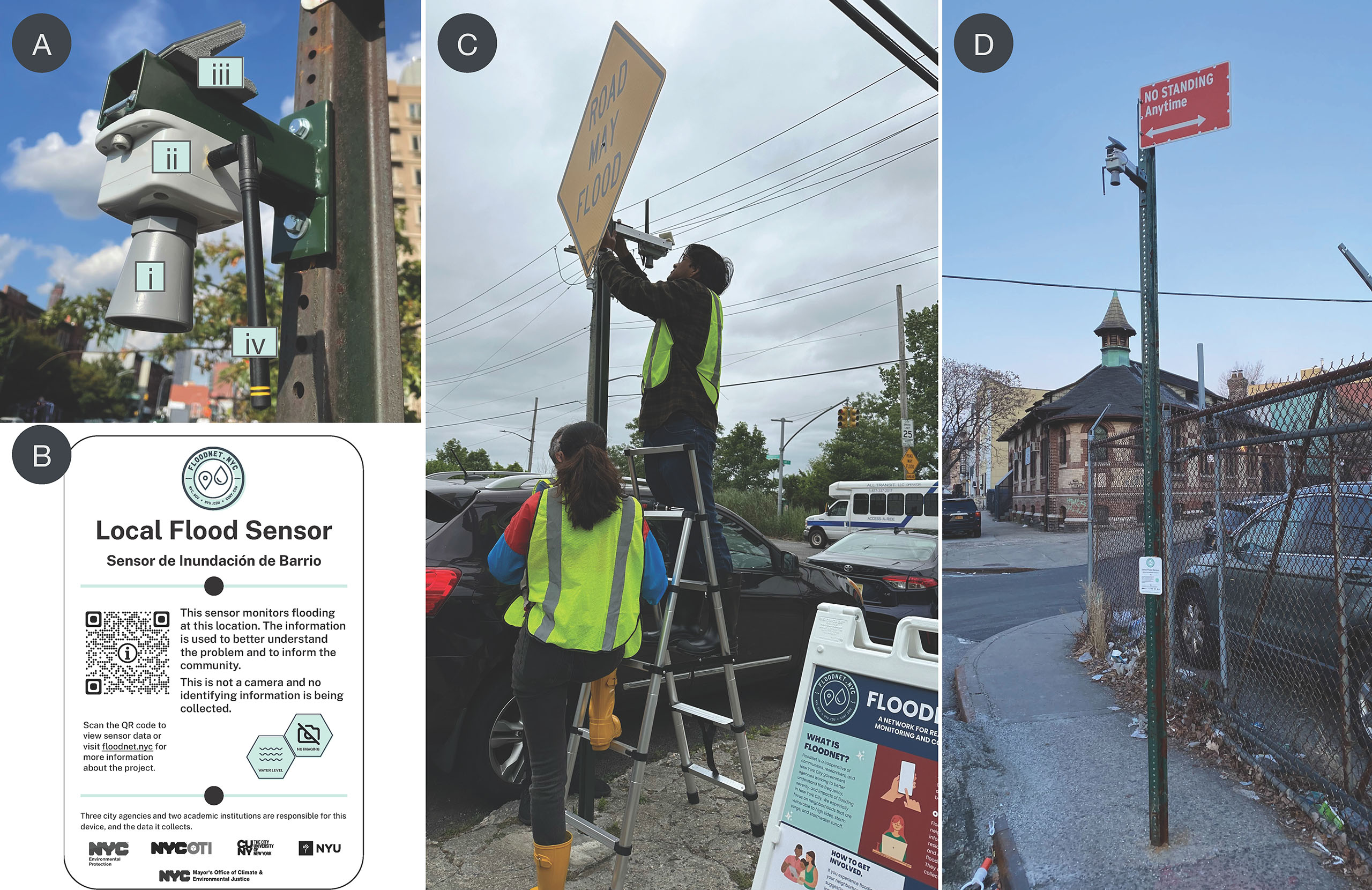

The solution: solar-powered, pole-mounted ultrasonic rangefinder modules assembled from off-the-shelf components at a cost of less than USD200 apiece. (Members of The Things Network NY assisted in the design of these devices. Plans are available from FloodNet's Github page.)

The techologies that made this possible: LoRaWAN and The Things Network.

Once a minute, a radio unit in each sensor module sends a single item of encrypted data to the network of gateways (any gateway can handle any remote sensor as long as the sensor is located, in this densely built environment, within about 2 km of the gateway). Data from the gateways is forwarded through The Things Network to project servers hosted by New York University, from which the data is made public over the internet using a variety of open-source tools such as Docker and Grafana.

FloodNet's plans for the future include expansion of the network to provide finer-grained coverage of the five boroughs and an iteration of sensor design to improve performance and lower the cost even further through manufacturing at scale.

Projects such as FloodNet show how the "smart city" concept can become a practical reality through the adoption of appropriate technologies. For a complete account of FloodNet, including insights relevant to similar efforts, see the FloodNet tech paper.

Photos from the full FloodNet report. (A) Closeup of the FloodNet sensor, showing the (i) ultrasonic sensor cone, (ii) sensor housing, (iii) solar panel for battery charging, and (iv) antenna for data transmission. (B) Signage that is installed with each sensor. (C) FloodNet engineers installing a sensor in the field.(D) FloodNet sensor and sign installed on a U-channel pole in the Bronx, NY.